|

| 電解機能水技術領導者 |

In a major blow to the beverage industry, all four cities that voted on soda taxes yesterday passed them in landslide victories.

San Francisco, Oakland, and Albany, California, voted in ballot measures that would levy a penny-per-ounce tax on distributors of sugary drinks. The people of Boulder, Colorado, also said yes to a 2-cent-per-ounce excise tax on distributors.

"This is an astonishing repudiation of big soda. For too long, the big soda companies got away with putting profits over their customers’ health," said Jim Krieger, the executive director of Healthy Food America. "That changed tonight."

In San Francisco and Oakland, the soda tax measures passed with 62 percent support. In Albany, it passed with 71 percent, and in Boulder, with 55 percent.

The stakes this year were high, for the beverage industry and for the philanthropists like former New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg, who invested millions in campaigns in favor of the taxes. The soda industry, which has seen slumping sales in recent years, has been terrified that more communities would follow the two cities that already have taxes on sugary beverages (Berkeley and Philadelphia) and approve levies of their own. The public health community, meanwhile, was desperate to build on the soda-tax momentum.

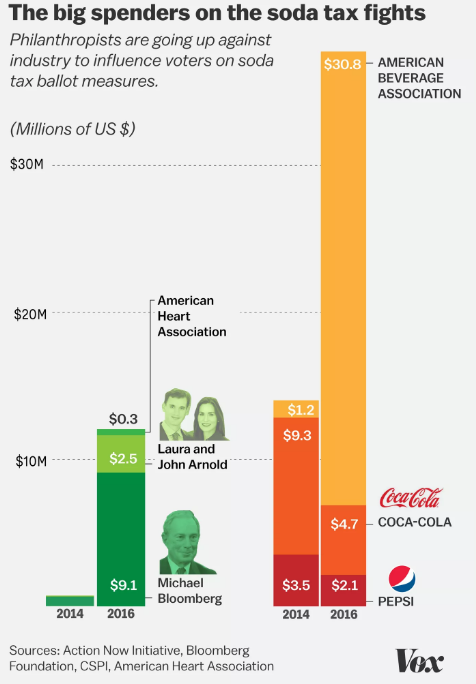

In the lead-up to the vote, spending on lobbying for both the pro- and anti-tax sides shot up astronomically in 2016 for what some have called the "most expensive city-level ballot initiative in US history."

Since 2014, when Berkeley, California, became the first US city to pass a soda tax measure at the polls, the soda industry — mostly represented by the American Beverage Association, as well as the major players (and ABA members) Coca-Cola and Pepsi — has more than doubled its spending on lobbying and campaigning against soda tax initiatives, from $14 million to $37.7 million.

Meanwhile, Bloomberg and Laura and John Arnold, billionaire philanthropists who have identified soda taxes as a potentially impactful public health measure, along with the American Heart Association, have opened their pocketbooks much wider, giving 17 times more money in 2016 than in 2014 ($12 million, up from $720,000) to this fight.

To put the spending into perspective, the dollars thrown at the battle over sugary drinks taxes this year — about $20 million in California alone, according to the Center for Science in the Public Interest — outstripped the $18 million in PAC donations to the federal election in the state.

It's not clear how much soda taxes will impact health

Health researchers have known for years that high-calorie, nutrient-poor beverages such as soda have been major contributors to the obesity epidemic. They give people big, quick doses of sugar with little accompanying nutritional benefit or satiety.

The basic idea behind sugary drink taxes is this: These beverages are a modifiable component of the diet, and making drinks like soda more expensive through taxation might help reduce consumption, improve awareness of the health harms they carry, and nudge people to choose lower- or no-calorie beverages instead.

Other jurisdictions, like the United Kingdom, Mexico, Denmark, and, again, Berkeley, already have similar taxation schemes in place. They each work a little differently, but they share a common goal: Raise the price of sugary beverages to drive down the amount people drink and, in turn, reduce the rate of obesity.

I asked several researchers who are studying how soda taxes impact public health whether this type of policy can really reduce obesity.

They all pointed out that it's hard to know that right now, since so few cities or countries have managed to get these policies into place (again, due to that fierce opposition from the soda industry).

Preliminary data from Mexico and Berkeley — where taxes have been implemented in the past two years — have shown declines in sales of sugary drinks. In Mexico, in particular, the reduction was greatest among low-income households, which also happen to be the groups most affected by obesity, according to a study published in BMJ in January.

But some researchers believe the taxes have real limitations in fixing a problem as complex as obesity.

For one, the taxes usually don't apply to all caloric drinks that people love. In the UK case, for example, pure fruit juices and sweet milk-based drinks, which can have just as much sugar as soda (or more), won't be taxed. So consumers will still have options that are potentially cheaper, but still calorie-dense, once the tax is imposed, said Roland Sturm, a senior economist and professor of policy analysis at RAND.

The taxes typically only add a few cents' cost to a beverage. "Don’t expect small taxes to make a big splash in reducing obesity," Sturm said.

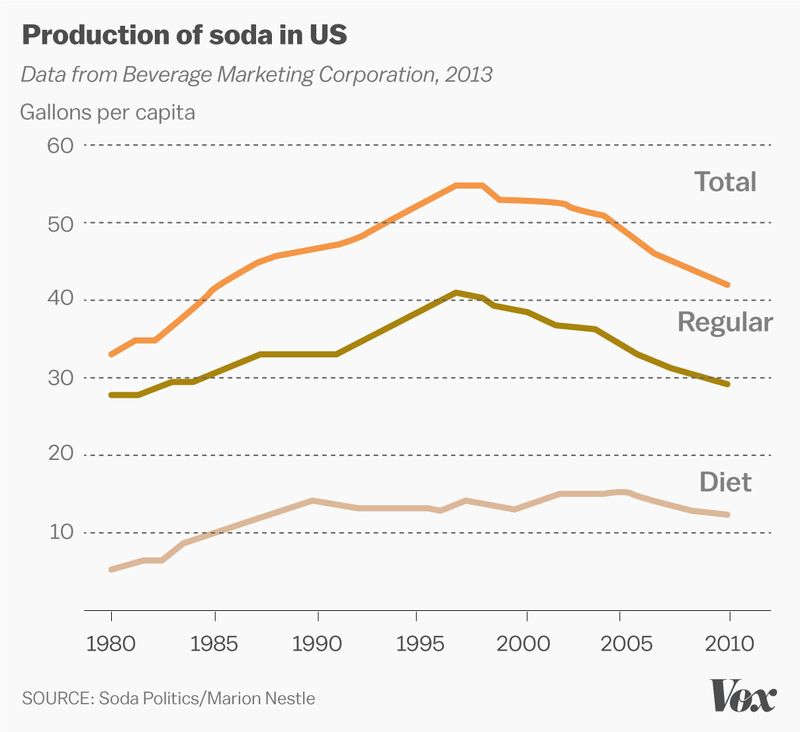

Marion Nestle, a New York University professor who wrote the book Soda Politics, said that it's also hard to disentangle the impact of taxes from the overall trend in declining rates of soda consumption. In the US, for example, soda consumption has been dropping since the late 1990s. In Berkeley, "consumption rates were low to begin [much lower than the national average] … so measuring a further decline won’t be easy," she added.

What's more, sugary drinks are only one source of added dietary sugar, and taxes on them haven't yet been linked to marked health improvements, said Shu Wen Ng, an associate research professor in nutrition at the University of North Carolina who co-authored the BMJ paper. "It will be a while before we expect to see health effects — like weight change, metabolic changes — as these changes require persistent changes over time to occur."

Ng pointed out that the obesity epidemic crept up slowly and insidiously. Reversing the trend will take time. "It will also take more than just a sugar-sweetened beverage tax," she said.

Soda taxes can be helpful in other ways

Even if soda taxes don't immediately change health, they do have other benefits.

First, they can raise awareness about the health harms of drinking what is essentially nutrient-bankrupt liquid sugar. "Taxes generate a vast amount of media discussion of the effects of sugary drinks on health," Nestle pointed out.

Taxes also help shift social norms, said Sturm. Consider tobacco: Increasing the price of cigarettes through taxation was one of the biggest contributors to driving down the smoking rates. "Smoking rates didn't drop immediately, and taxation had a small effect on consumption immediately," he said.

But eventually the taxes had an effect, "and with fewer people smoking … it becomes less acceptable to smoke, so it was a feedback loop." He said the same could happen with soda consumption.

The money raised from the taxes can be used to support other obesity-fighting policies and raise revenue for cash-strapped communities. In Britain, revenue from the drink taxes will fund childhood obesity interventions, such as sports programs in primary schools. In Berkeley, the money goes to children's health programs in low-income areas that are battling particularly high rates of childhood obesity. Philadelphia’s tax will fund an array of community and education initiatives, including universal pre-kindergarten classes, building new community schools, and improving recreation centers, parks, and libraries throughout the city.

The taxes have also encouraged companies to change their manufacturing practices by offering more lower- and zero-calorie options.

"While a sugar-sweetened beverage tax will not be a silver bullet, if it results in even more moderate changes in obesity, that would be very welcomed by public health advocates," said Brian Elbel, an associate professor in popular health and health policy at the NYU School of Medicine. He added that the tax may be just one of the many policy tools in the toolbox.

As Elbel said, "We have to keep looking for policies that can have even small but cumulative impacts."

Is soda the next tobacco?

These wins for public health could be a harbinger of yet more taxes to come. According to Healthy Food America, at least 12 cities and six states are seriously considering sugary drinks taxes of their own.

"This is not different from tobacco taxes," University of North Carolina nutrition professor Barry Popkin said, noting that several states took the lead with cigarette taxes and then the federal government followed suit.

Indeed, the fight over soda taxes is looking eerily similar to the tobacco wars.

Like the misinformation campaigns spread by cigarette companies for years, we now know the sugar industry and soda companies have been sponsoring health groups and obesity and nutrition researchers with the goal of distorting science and how it’s communicated to the public.

Meanwhile, concerned researchers and health officials — just as they did with cigarettes — have started to worry that some of the food on offer in America is a health hazard in need of government intervention.

Right now it’s clear that Americans — in the states that voted last night at least — believe government has a role in regulating soda.

In a statement, the American Beverage Association acknowledged as much: "We respect the decision of voters in these cities. Our energy remains squarely focused on reducing the sugar consumed from beverages — engaging with prominent public health and community organizations to change behavior."

No matter what beverage makers do next, America's view of soda is certainly changing. Before Berkeley passed a soda tax in 2014, cities and states across the US had tried — and failed — 40 times to get their own in place.

The new momentum on the side of public health is unprecedented. "I think people are associating sugar with items like alcohol and tobacco," philanthropist John Arnold told Vox, "and they understand the negative aspects of them, and why they are taxed."

繁體中文

繁體中文  简体中文

简体中文  English

English